When researching ‘The Rugs and Carpets of Fallingwater,’ for our Summer 2018 issue, it immediately became apparent that given the current popularity of Moroccan carpets, an article about mimicking the look of Fallingwater would have to be written. A survey of the pages of ‘Fallingwater’ by Lynda Waggoner reveals photographs of room after room of either white, fluffy, and inviting Beni Ourain rugs or more lively and red colored embroidered flatweaves; both of these readily available in today’s marketplace. But is it right, (or Wright) simply to duplicate the aesthetic?

It should be emphasized that the Moroccan carpets originally used at Fallingwater were not the result of a master plan. The house was built as a weekend retreat and the owners intended a casual relaxed vibe. Morroccan carpets—berber as they were called at the time—certainly fulfilled the desire for informality; it also did not hurt that the style was quite popular in the late 1930s, when Fallingwater was completed. In 2018, Moroccan carpets are experiencing another cycle of popularity and for that reason it is safe to answer ‘Yes!’ it is acceptable to duplicate the aesthetic. In fact, it is quite easy today to duplicate the look at a variety of price points and degrees of authenticity, yet this is not solely a simple matter of copying a look.

It is easy to try to summarize all that Frank Lloyd Wright was in neat and tidy Twitter-size morsels. But this does not do Wright, Fallingwater (or any of his structures for that matter), or the Kaufmann family who built it adequate justice. A casual observer—as this author once was—may see the Moroccan carpets and think ‘Oh, this must have been Wright’s intent.’ It was not. At the time Fallingwater was built Wright’s career had been in decline and his intent, to be blunt, was to secure work, meaningful of course, but still work. Fallingwater proved to be the extraordinary commission that revived the career of ‘the world’s foremost architect,’ as marketing copy of the F. Schumacher & Co. would later describe Wright on the licensed fabric line they produced in 1955. Though it is correct to classify Wright as a master, even a creative genius, at his core, Wright also wanted to make money. In considering whether it is ‘wright’ to duplicate the look of his masterpiece, Fallingwater, it is important not to overlook that fact. It is also essential not to forget the client.

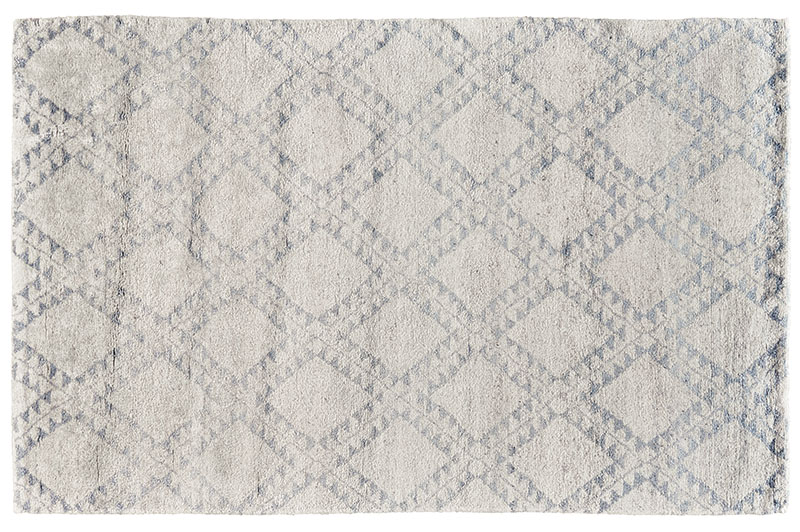

K368 from Bazar du Sud.

Take the example of the two carpets shown here from Bazar du Sud. Either could fit as comfortably at Fallingwater itself, as at a home seeking to embody the feel, the visual essence of that place. As they are also currently popular, including them fits the spirit of the modern home as an embodiment of au courant living. And isn’t this the most salient point, that what’s right has to take into account where we are now? Of being right in perspective.

Modern living is not, however, all glamorous multi-million dollar homes or perfectly coifed spaces plucked from the pages of design magazines or Instagram. Surely it is for some, but for many, or indeed most, there is a degree of mediocrity that must be observed; this is not meant in a derogatory way. Wright once stated, ‘Mechanization best serves mediocrity.’ Again, while it does sound elitist, Wright does not intend to convey conceit, rather the contrary. He viewed ‘mechanization’ in a twofold way; as the spread of information outward from purely academic circles, and the automation of manufactured goods. Mass produced goods, by their nature, must be of average quality — the very definition of mediocre. From another perspective: if everyone has a berber, or Moroccan, or any other kind of carpet in their home, the average aesthetic… .

Early twenty-first century vernacular tends to assign negativity to any adjective not hyperbolically amazing, so unfortunately to call something ‘mediocre’ in this time is to be perceived as slightly derogatory, even if that is not the intent. So, while the following carpets may be mass produced, and dare one say ‘average’, as successful purveyors of rugs and carpets such as Feizy know: average is ok, and moreover, profitable, easy to use, and highly saleable.

Feizy’s Abytha Collection (pictured above) perfectly illustrates the look one might try to duplicate and it provides said aesthetic at a price point more approachable than others. Furthermore, given it is a mass-produced Indian-made carpet, it possesses features many modern (read: average) consumers have come to expect e.g. size availability from roughly 6'x9' to 10'x14' (1.83m x 2.74m to 3.05m x 4.27m). The benefit of course is that a consumer need not keep looking if the individual carpet they see isn’t the right size, the right size can be ordered. This is in contrast to the nature of Moroccan production broadly speaking and it returns to what Wright was discussing. Authentic Moroccan carpets are beautiful but the appreciation of their nuances can only be so widespread. Beyond that, the needs of others who like the look but don’t necessarily care about authenticity need to be met. As Feizy states in their marketing copy for the Abytha Collection: ‘…wool and viscose fibers crisscross in casual geometry, proving upscale looks can be both luxe and durable. Handknotted in India, Abytha is a designer’s dream, easily commanding but never demanding your guests’ attention.’ For both designers and direct customers, often the ease of use brought about by ‘mechanization’ is more appealing than the requirements of purchasing and living with more authentic goods.

Both carpets from Bazar du Sud are a visual delight, yet for the uninitiated, the irregularly of their construction may be off-putting. In today’s context, to balance the desires of those who want to reproduce the look of Wright—and others—it might be wise to look beyond the visual and think of what Wright or his clients would do now. Would they choose Moroccan again as they are en vogue, or would they choose something else?

The answer is unknowable, but to touch upon a common theme of ‘educating consumers’ and relate it to Wright’s mechanized spread of information one must come to accept that an educated consumer may, and should realize what product, what rug or carpet, is best for them. Successful rug dealers already know this. By catering to the needs and wants of their clientele, they have been able to provide the right look, at the right price, with the right characteristics to meet the demands of the modern home dweller. Whether or not Wright would approve would probably have depended on the relative success he was experiencing at the time.

Images courtesy of their respective companies.