Rug Insider takes you behind the scenes to examine the making of a Nepali-Tibetan carpet as Josephine Ford talks about her process and her collaboration with London’s FLOOR_STORY. Follow along as we offer a peek behind the romance, into the toughness—the strength—of Nepali-Tibetan weaving.

There is without any hesitation the ability to say the rug industry loves to romanticize. It also happens to be the case that details—while perhaps less romantic—add insight and understanding while also building a deeper romance, if one will allow the theatrical language. This flowery, perhaps hyperbolic introduction is in contrast to the style of artist Josephine Ford who describes her more recent work as “creating with the ambition to remove unnecessary detail. Reduce, reduce, reduce until you’re left with something more primal—an essence.”

One example of this is a pair of carpet designs made in Nepal by Floor Story of London. Snake and Moth described by the artist severally as “Aztec Gemini love story” and “Art Deco double vision meets Chinese rug’ reflect Ford’s ‘fame for fashioning both strong designs and innovative visual direction for fashion houses, musicians, record labels, restaurants, bicycle designers and book publishers.” This is the mind behind the creation of Moth and Snake, the latter of which Rug Insider now follows from creation to installation, briefly discussing the details, enriching the character—albeit in an admittedly cursory, non-exhaustive, and non-definitive manner.

“Initially I was drawn to the idea that traditionally rugs were used to tell a story and that they often carried family motifs and meaning. I carried this idea into two designs that portray animals meeting in the middle, as if they are in love or permanently connected.” says Ford. “I conceptualize my work in a very analog way. Contemplating, drawing, cutting, pasting, painting or weaving. I bring in digital tools if I feel they lend themselves to the work.”

It is with one of these digital tools that the vast majority of carpets produced in Nepal today are realized. Regardless of original artwork, before weaving can commence a graph (Image F below) which the weavers will follow must be made. More often than not this graph is produced via software such as Galaincha. A visualization of the Snake design—another feature of the software—previews for the viewer what the finished carpet will look like. These features of Galaincha, amongst many others, help minimize miscommunication between all levels of rug production and reduce waste by calculating with a high-degree of precision the quantities of materials used. This is especially important for boutique firms such as Floor Story and their manufacturer Lama Carpet and Handicrafts, who don’t have the luxury of waste mitigation through volume as is the case for higher capacity producers and importers.

Himalayan Highland Sheep’s Wool is the most prized for making carpets in Nepal. Known for its high lanolin content, long staple, and supple hand, it provides for a beautiful and hard wearing finished carpet.

Once a design such as Snake is created, rendered in digital form, and approved, the manufacturing process can begin. One of two defining characteristics of a true Nepali-Tibetan carpet is the use of Tibetan Highland Sheep’s Wool—the most desirable for carpet making in Nepal. Raw wool can be processed into yarn either by hand or by machine. For larger concerns this is done in-house, while smaller operations often buy their wool yarn from a wool house; dyed or undyed, again depending on the facility and their individual requirements. Regardless, once the yarn is dyed and balled, the next step of the process can commence.

Weaving of a carpet in Nepal is done on a vertical loom, made today of steel which provides strong stable support ensuring a reliably square carpet free of dimensional irregularities. Prior to the first knot being tied, however, the loom must be warped. That is, the cotton (generally) warp yarns which form one half of the carpet’s foundation, must be stretched tight on the loom. The other half of the foundation, the weft—also generally cotton—will be inserted as the knotting of the carpet progresses. While some will refer to the process of making a rug weaving, others call it knotting, and in truth both occur.

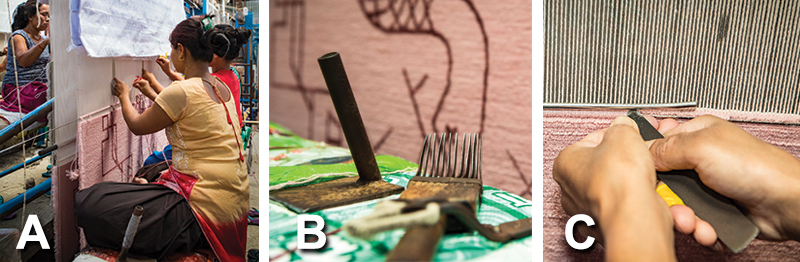

The other defining characteristic of Tibetan weaving is the unique knot structure which is tied around a metal rod during production. This is perhaps the most outwardly visible characteristic, one that defines Tibetan weaving— which came to Nepal via Tibetans fleeing Tibet starting in 1959—regardless of country of manufacture today. The diameter of the rod (shown in Image A) determines the finished pile height. Once a section of knots—approximately 2'6" to 3'0" (76-91cm) wide—is tied by a weaver the knots are beaten into position using a weighty narrow-headed hammer (Image B, background). The rod is then cut from the yarn which has been tied around it using a knife (Image C). Depending on the angle at which the loops are cut the characteristic “ridge and valley” texture of a Tibetan weave carpet will be more or less pronounced. Alternatively, the rod can be pulled from the knots leaving intact a loop pile, with infinite combinations thereof also possible.

After the rod is removed, the row of knots is further compacted and locked into position by another weighty tool, this time a metal comb (Image B, foreground). Once a row of knots is complete, weft yarns—the second component of the foundation—are passed through the warp via a shuttle (Image D). Weft yarns provide lateral stability to the carpet and may be woven (crossed) or not (uncrossed) between the warp depending on the desired finished texture of the carpet. The latter being more rigid and square, the former more blanket-like, Snake is uncrossed. Knotting then progresses row by row until the entire carpet is completely woven (Image E).

Whether a carpet is designed with fringe or without, the end of the carpet must be finished as to provide stability. This is accomplished by weaving with warp and weft a narrow kilim band after the last row of knots (Image F), though it should also be noted a carpet is started on the loom in a similar manner prior to the first row of knots. Just as the knots are compacted into place by the metal comb, so too is the kilim as is shown in Image G.

Once a carpet is completely knotted and its ends fixed, it is cut from the loom (Image H). This is the ceremonial end of the making of the carpet, but much like fine cabinet making, one must first make an object before it can be finished, acknowledging it is the finishing which brings out the final beauty of the carpet. While many of the steps heretofore—wool processing particularly if done by hand, dyeing again if done in small batches with natural dyes, and especially weaving and knotting receive the most romanticized treatment in the marketing of handmade carpets, without proper finishing a carpet is simply incomplete.

At this point, the carpet, freshly cut from the loom, is lain on its face and a worker uses a large steel needle to poke at the back of the carpet. This step aligns knots, pushes any loose yarns more firmly into place, and generally tidies the appearance of the carpet (Image I). It is then given the treatment that may prove to be most astonishing for the casual rug fanatic: the back of the carpet is burned. As wool is naturally fire retardant, it will only burn when exposed to direct flame (Image J) which is done with a propane torch. This singes all of the fine extraneous wool fibers providing the carpet a clean and tidy appearance. Once the entire carpet is singed, the charred wool residue is swept from the back (Image K).

Whether a design is heavily sculpted with a high degree of relief, or if the design is merely scissored to outline the design—bringing it into sharper definition—scissoring or shearing the carpet is required to bring a uniform aesthetic to the face of the piece. The latter is the case with Snake as shown in Image L.

Washing is a critical step of finishing and takes place toward the end of the process. A rolled carpet is first submerged in clean water (Snake is shown being submerged by manufactory owner Raj Lama (right) in Image M) allowing the wool to fully ‘wet’ or absorb water. As Himalayan Wool is naturally very high in lanolin content it possesses a degree of water repellency which while great for cleaning quick spills, means a carpet must be given time to allow the water to penetrate the fibers. Once thoroughly wetted, the carpet is placed flat on the washing floor where it is repeatedly washed either with water only or with natural or chemical cleaning agents, again depending on individual requirements and methodologies, before being rinsed thoroughly with clean water (Image N) and squeegeed with a large wooden paddle (not shown). After rinsing the carpet is left in the warm Himalayan sun to dry (Image O).

Further steps to finishing such as binding the fringe to the back (if no visible fringe is specified as is the case with Snake), trimming the edges and overcasting (the tightly wound wool yarn on the sides of a carpet), and if necessary blocking the carpet to make it square remain but are not shown. Furthermore, it should be reiterated this is but a cursory explanation of the process in order to provide for that ‘deeper romance’ noted at the outset. Once finishing is complete, the carpet can be shipped to the customer, ultimately making its way onto the floor of those with distinguished and varied tastes.

“I intended to craft something that could appear as something else from different angles.’ says Ford of both Snake and Moth. ‘I think it is the meaning behind that is more important than how the designs can be explained though. They have a story to tell and it’s up to you how you read it. I wanted rugs that didn’t intrude, but rather that lifted and supported the room. I am very proud to work with Floor Story. They feel a little romantic, but are tough too and it is this double meaning that is at the heart of my collection.”

josephineford.com

floorstory.co.uk

Photography: Image of Josephine Ford courtesy of the artist. Image of Snake in situ courtesy of FLOOR_STORY.

Documentary in production images by Prabal Ratna Tuladhar for RUG INSIDER.